What follows is the presentation I gave this past Saturday at the Trianle Conference on Peak Oil and Community Solutions. Much thanks to Peter Taylor and the Hrens for organizing the effort. More to come on the overall event. My piece of the puzzle entailed facilitating discussion about the affects of peak oil on food production. Thanks also to Tami Schwerin of The Chatam Marketplace cooperative with whom I worked in two separate sessions of discussion on this issue. I was please to see so many people interested in how we will feed ourselves post peak oil; post green revolution.

An Introduction to Agriculture Post Peak Petroleum

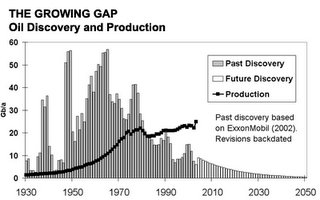

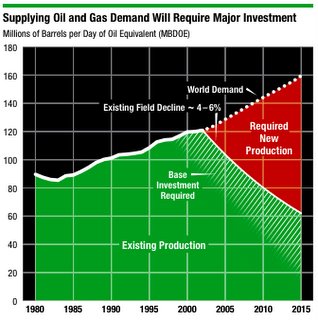

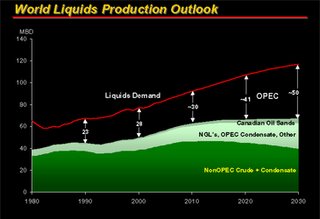

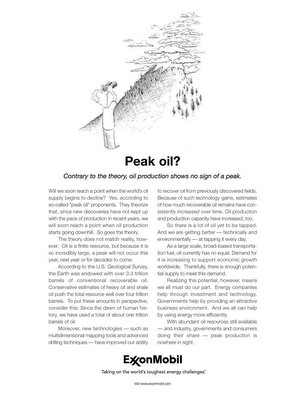

71% of the petroleum consumed in the United States is used to power transportation. This will be the sector of our society most noticeably affected as global oil production peaks sometime in the very near future. Last year’s temporary spice in the price of automotive fuel caused long lines and increased anxiety levels in North Carolina. Far more chilling though than the discomforts of an increase in the price of gasoline is the implications that a reduction in oil supplies will have on our ability to feed ourselves. Modern industrial agriculture requires on average 10 calories of fossil fuel to produce 1 calorie of edible vegetable food; 35 calories of fossil fuels for 1 calorie of beef and 68 fossil fuel calories for every 1 calorie of pork. Drs. David Pimentel of Cornell University and Mario Giampietro of the Istituto Nazionale della Nutrizione in Rome, Italy have provided data that shows “400 gallons of oil equivalents are expended annually to feed each American.” The three largest fossil fuel inputs relied upon by commercial agriculture break down like this. 31% of this petroleum is used to produce fertilizers. 19% is used to operate the machinery that currently replaces human and animal labor on the farm, and 16% is used to transport the food we eat. The average piece of food travels over 1500 miles before it reaches your dinner table. As the price of the oil doubles and triples ad infinitum the price of producing and transporting food from across the nation or in some cases across the world will follow suit. Let’s set aside facts like modern agriculture consumes 85% of the fresh water used in the United States or the fact that topsoil in this country is being depleted at best 30 times faster than the rate at which it is naturally produced. These are related issues but I’d like to focus today on the big three: fertilizers, mechanized labor and food transportation.

If you’ve read the July 2004, Harper’s Magazine article entitled “The Oil We Eat” by Richard Manning or Dale Allen Pfeiffer’s article “Eating Fossil Fuels” you probably have an even better understanding of the extent to which or food production system is based on fossil fuels especially oil. If you haven’t read them you should.

So if we know that the chemicals we use to fertilize our soils are going to become more scare and more expensive and if we understand that the labor of plowing and planting and producing our food will no longer be accomplished in the future by machines powered by petroleum and if we recognize that the idea of transporting food from far flung corners of the globe will not be possible in an era of increase fuel prices what are we going to do about it?

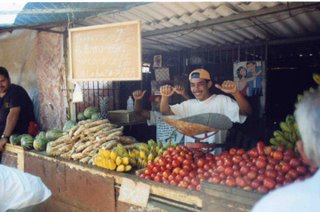

The 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union had a profound impact on one certain nation. Cuba was devastated by the event. Almost overnight the island lost its main source of petroleum and petroleum based products. 70% of its agricultural chemical imports disappeared. The effect during the first year of what the Cubans refer to as the “Special Period” was a 50% reduction in daily caloric intake resulting in an average of 30 pounds of weight loss per person in that country. Let me say that again the average Cuban lost 30 pounds during the first year that country was unable to continue with petroleum based agriculture. How did Cuba and its largest urban are react? The city of Havana has a population of over 2 million people. That’s far greater than any metropolitan area in North Carolina. In the period that followed the Soviet collapse Havana used a plan to create more than 8,000 urban gardens. Some neighborhoods and these are dense, urban neighborhoods, produce more than 30% of the food the residents eat. The Government of Cuba granted gardening rights to those willing to work the land of vacant lots in the city and planning laws began to place a high priority on food production. The population was decentralized to a certain extent but the transportation needed to carry food to cities such as Havana was decrease in large part because the food was grown inside these city or close by.

The caloric intake rate among Cubans has returned to a level near that of the late 80’s. By the way their infant mortality rate is now just slightly better than that of US infants and their life expectancy is on par with ours. A new documentary due out in April from The Community Solutions group explores the Cuban response to their drastic reduction in petroleum inputs

The caloric intake rate among Cubans has returned to a level near that of the late 80’s. By the way their infant mortality rate is now just slightly better than that of US infants and their life expectancy is on par with ours. A new documentary due out in April from The Community Solutions group explores the Cuban response to their drastic reduction in petroleum inputs

How about here in the U.S.? What would we look like 30 pounds lighter?

That’s kind of an amusing question to some extent but what would our children look like 30 pounds lighter? How well would they be nourished with out all the fresh Florida orange juice we take for granted or the lettuce from California that makes up the 3000 mile Caesar salad we had from lunch?

That’s kind of an amusing question to some extent but what would our children look like 30 pounds lighter? How well would they be nourished with out all the fresh Florida orange juice we take for granted or the lettuce from California that makes up the 3000 mile Caesar salad we had from lunch?

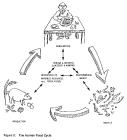

Let’s tackle these issues one at a time. I mentioned 31 percent of fossil fuel inputs in agriculture are used to created inorganic fertilizers. The solution to overcoming this dilemma is a return to the cyclic patterns that governed agricultural production before man harnessed the power of petroleum. Prior to cheap commercial fertilizers farmers relied on composted nutrients to build soil and produce crops. Kitchen waste, yard waste, animal manure and green manure or composted crops are all part of a possible return to a system that employs what some consider waste and returns to nature the rubbish we currently dump in our landfills. I watch people put trash bags full of organic material- leaves and grass clipping out at the street for the city to take and dump in the landfill and I wonder if they understand the amount of nutrients they could be returning to the soil. In former times humans utilized the slight excesses of these systems to produce food for themselves. The so called “green revolution” of the 50’s and 60’s substituted dependency on stewardship of these systems for dependency on chemicals likely to run short in the near future. We must go back to a pattern of returning theses nutrients to the soil. We must follow the cycles of flow not the linear pattern of input. We must compost like crazy.

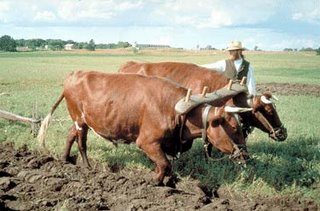

Next we have to deal with the issue of mechanized labor. In 1920 just over 30% of the population if the United States of America was involved in farming. By 1950 that number had decreased to 15.3%. In 1985 on 2.2 % of our population were active in the production of the food we eat. The work of growing crops has been turned over to machines that use oil as energy. What will happen as less and less of this oil-based energy is available?

I fully expect to a certain extent a return of human labor to the task of producing food. Perhaps those who currently push paper for a living will find themselves unexpectedly involved in future food production. I think animals will once again play a part in how we prepare for the task of raising crops. Animals come with their own share of needs and required care but they also reproduce.

I fully expect to a certain extent a return of human labor to the task of producing food. Perhaps those who currently push paper for a living will find themselves unexpectedly involved in future food production. I think animals will once again play a part in how we prepare for the task of raising crops. Animals come with their own share of needs and required care but they also reproduce.

Oxen have babies, tractors don’t. They also recycle food into manure that works well as a fertilizer. This arrangement is profitable even for the backyard gardener. I have 3 chickens despite my limited amount of property and close proximity to our downtown. My hens provide my growing family with fresh, chemical free eggs and they recycle my uneaten food into wonderful composted fertilizer for the garden. They eat bugs and are fun to watch but raising urban chickens is a topic for another day. Suffice to say that animals of all kinds have been and will again be used to store energy and recycle nutrients humans are unable to process. Green manures or composting cover crops are another way to build soil without using chemical fertilizers. Growing plants that stabilize unused soils and fix nitrogen from the air that can then be turned back into the soil to replenish the nutrients lost is a great way to naturally build fertility.

Oxen have babies, tractors don’t. They also recycle food into manure that works well as a fertilizer. This arrangement is profitable even for the backyard gardener. I have 3 chickens despite my limited amount of property and close proximity to our downtown. My hens provide my growing family with fresh, chemical free eggs and they recycle my uneaten food into wonderful composted fertilizer for the garden. They eat bugs and are fun to watch but raising urban chickens is a topic for another day. Suffice to say that animals of all kinds have been and will again be used to store energy and recycle nutrients humans are unable to process. Green manures or composting cover crops are another way to build soil without using chemical fertilizers. Growing plants that stabilize unused soils and fix nitrogen from the air that can then be turned back into the soil to replenish the nutrients lost is a great way to naturally build fertility.

Lastly we must recognize the great distance most of our food travel to meet us. This is what I believe is the most readily fixable problem within our current food production system. The idea that we in North Carolina are dependent on farmers in California to produce our lettuce is ridiculous. We might be obliged to once again enjoy the crops of the season and not be spoiled by pineapples in January and oysters in June by how nice it was to experience the seasons not solely by the temperature and length of day but also by the food available during specific times of the year. Regardless, we will be forced to make due with what we are able to produce locally as food and fuel prices increase. Relocalization of our food production will not be a luxury it will be a necessity.

In 1943 Americans took food production out into their own backyards. The nation’s population that year boasted 20 million Victory Garden. I find it personally humorous the United States Federal Government didn’t initially support these personal gardens because they didn’t trust the average American to make good use of his or her resources. During that very same year however 70% of the vegetables consumed on the home front came from Victory Gardens. In 1943 Americans grew 70% of the vegetables consumed domestically. There’s a statistic I find hopeful. I think localized food production can be separated into concentric categories base on the distance of travel from producer to consumer.

The closet possible food producer is of course you. Home gardening can be extremely productive and provide food at incredibly savings even in our current price structure.

The ability to produce some or much of what you need to eat is an incredible form of freedom. It empowers a household to begin reusing its compostable waste, it cause the family cultivate a closer connection with natural systems and it unplugs those willing to garden from the current agricultural system that has put in place a dependency on fossil fuels bound to cause us problems in the future post peak oil. In other words Monsanto take a hike.

The ability to produce some or much of what you need to eat is an incredible form of freedom. It empowers a household to begin reusing its compostable waste, it cause the family cultivate a closer connection with natural systems and it unplugs those willing to garden from the current agricultural system that has put in place a dependency on fossil fuels bound to cause us problems in the future post peak oil. In other words Monsanto take a hike.

Community gardens are the next closest food production cycle. They make use of cleared land and available sunlight to increase the amount of food producible in given area. Shared work and responsibility can be reward in ways that exceed crop yields. Much can be learned from others.

I am in the process of fostering a new garden in my community and I have been surprised at who has come out of the wood work with great gardening knowledge or at least great enthusiasm. It is a reason for somewhat separate individuals to come together for a common cause. I hope this is even more true in the future.

I am in the process of fostering a new garden in my community and I have been surprised at who has come out of the wood work with great gardening knowledge or at least great enthusiasm. It is a reason for somewhat separate individuals to come together for a common cause. I hope this is even more true in the future.

Slightly further from the consumer is the local food producers who are most likely farmers whose sole employment it is to grow food. They will again thrive on the edges of urban or semi-urban areas. Those with the land and know-how to grow crops without artificial energy inputs will be in great demand.

In Cuba farmers now earn greater wages than engineers. Community Supported Agriculture or CSA programs are a way for you to begin to support theses farmers. A weekly visit to your farmer’s market is another. And then there’s the local food co-op.

In Cuba farmers now earn greater wages than engineers. Community Supported Agriculture or CSA programs are a way for you to begin to support theses farmers. A weekly visit to your farmer’s market is another. And then there’s the local food co-op.

Outside of local farmers I think we will continue regional production of crops well suited to our climate. And an additional step further beyond that I think national and international food trade will continue in ever-decreasing amount. In the future I think the large majority of what we consume will come from a fairly small radius.

Have you ever boiled a frog? If you drop it into water 212 degrees Fahrenheit the frog will obviously protest and try its best to get out of the pot. If however you place the frog in lukewarm water and very slowly turn up the temperature the frog will eventually roll its eyes back into its head and die. Why such a horrible story in the middle of me presentation you ask?

The United States will most probably not experience a Cuban-like period of dramatically reduced petroleum agricultural inputs. I think instead that we will see a rocky decline in available energy and likewise an unstable decline in cheap food from afar. It won’t happen overnight. Will we notice and take action? Or will we experience a gradual increase in scarcity and wait until too late to begin the task of growing our own food? I am hoping to help avoid tha. I’d like your help.

Normally after I’m finished talking people will ask me, “So what are we suppose to do”?

Here is the list I give them.

First, educate yourself. Don’t believe everything anyone says even me. Read, go online, pay attention to where your food really comes for, listen to others, educate yourself.

Second, grow your own food and by that I don’t mean try and provide all your family’s calories this year. You overload trying to do that. But pick a few things to grow- a couple of tomatoes, peppers, some potatoes… m maybe some beans and learn and increase each year. The important thing is to get started. Start small and dream big. But start now.

Third, work towards a community garden. Look for unused sunny property and neighbors who might be willing to help. There are resources online and maybe in your community already. Get together with neighbors and build an effort to grow food.

Forth, support your local farmers. You can do that by visiting the farmers market looking into CSA (community…) joining your local food cooperative. Try asking you local restaurant if they buy from local food producers- put the bug in their era that you as a patron are interested in that. Ask your waitress for a chicken bag and tell her that your unrecognizable leftovers will be taken home and composted by your very own chickens. I promise you’ll get a reaction.

Lastly don’t rely on others as the only ones to provide your basic needs. You might not want to become a farmer or a chicken rancher or a rainwater collection specialist but understand the basics of how to take care of yourself, your family, your friends and the environment around you. This return to responsibility will I believe be the beginning of a better tomorrow.

Some people believe agriculture itself is unsustainable. I believe we’ve made this bed and now we have to find out how to responsibly lie in it. John Jevons recommends 60% of crop lands be dedicated to producing soil amendments but the use of dual purpose seed and grain crops is acceptable to his practices. Do your food producers turn more than half of their crops back into the soil? How about water use; do they divert waterways to irrigate otherwise unfarmable land? Is the idea of shipping food from

Some people believe agriculture itself is unsustainable. I believe we’ve made this bed and now we have to find out how to responsibly lie in it. John Jevons recommends 60% of crop lands be dedicated to producing soil amendments but the use of dual purpose seed and grain crops is acceptable to his practices. Do your food producers turn more than half of their crops back into the soil? How about water use; do they divert waterways to irrigate otherwise unfarmable land? Is the idea of shipping food from